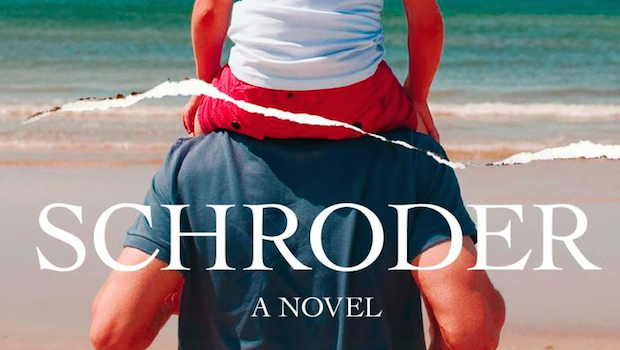

Schroder by Amity Gaige

| Press reviews | Buy the book | Have your say |

Blurb: Attending a New England summer camp as an adolescent, young Erik Schroder – a first generation East German immigrant – adopts a new name and a new persona – Eric Kennedy – in the hopes that it will help him fit in. This fateful white lie will set him on an improbable and ultimately tragic course. Schroder relates the story of Eric’s urgent escape years later through the New England countryside with his six-year-old daughter, Meadow, in an attempt to outrun the authorities amidst a heated custody battle with his wife, who will soon discover that her husband is not who he says he is. From a correctional facility, Eric surveys the course of his life in order to understand – and maybe even explain – his behaviour; the painful separation from his mother in childhood; a harrowing escape to America with his taciturn father; a romance that withered under a shadow of lies; and his proudest moments and greatest regrets as a flawed but loving father. (Faber and Faber)

Janet Maslin, The New York Times

“[The] escapades are so unthreatening that it’s genuinely jolting when “Schroder” tilts toward a police chase and criminal prosecution. To her credit, Ms. Gaige has delicately mentioned the plot point that could potentially destroy Eric. But she hasn’t harped on it, so it resurfaces as a terrible surprise. And the reader is left to dissect a book that works as both character study and morality play, filled with questions that have no easy answers.”

Sadie Jones, The Guardian

“There is a dark undertow to the book and to its narrator. He is not what we fear, but not quite what he would like to think he is, either, and the parallels with Nabokov are more lyrical than the signposts of foreigner, road-trip and kidnap. They lie in Schroder’s immigrant’s view of America, the beautiful yet dissociated descriptions of the landscapes through which he drives with Meadow. English is his second language, which animates the flow of his narrative voice. He describes postwar Berlin as a “mirror image of the splintered whole … divided fractiously … a little smackerel of it even going to French …” with a Nabokovian playfulness. This is not to say the novel is derivative; it is contemplative, poetic certainly, but the narrative is urgent and concise and Gaige’s storytelling effortlessly spontaneous.”

Suzi Feay, The Literary Review

“e feel that Meadow is in no danger from Eric’s wrath (though she is from his well-meaning incompetence). If the novel interrogates marital love, it also celebrates the parental variety. Meadow is poignantly (but never cutely) portrayed, with her teeny clothes, funny sentiments and penchant for putting glittery stickers on things. Eric loves her to distraction but also, as an adult, gets bored with her company. ”

Jonathan Dee, The New York Times

“The essence of the ersatz Rockefeller/Kennedy character is of course an epic, pathological narcissism, and this Gaige gets impressively right — which may be something of a Pyrrhic victory, since Schroder’s role as narrator ensures that his story will have only one fully developed character. That his wife and even his beloved daughter never quite come across as real people is no criticism of Gaige; it’s simply the fundamental compromise her material requires her to make.”

The Economist

“Ms Gaige’s main achievement is to inhabit her protagonist so thoroughly that the reader cannot help but empathise. Eric is by turns insightful, funny, bizarre and irresponsible, at once self-deceiving and self-aware. ”

Kate Saunders, The Times

“A brilliant exploration of identity and belonging, and Gaige’s writing is beautiful.”

Elizabeth Buchanan, The Sunday Times

“Brilliantly eliciting sympathy where, theoretically, none is deserved, this is a tense, ambitious, bravura exploration of the physical and psychological limits of identity — how we are seen by others, and what we make of ourselves. It is also a poignant love letter to a daughter.”

Ron Charles, The Washington Post

“Adventure or abduction, his tale makes for a fascinating mixture of candor and self-justification, a testimony that glosses over the most harrowing and negligent behavior with buoyant good cheer and professions of love. And what makes it all deeply tragic, instead of merely psychologically thrilling, is that Schroder really does adore his daughter. His descriptions of their little science experiments and charming repartee are moments of bliss that any parent will resonate to. ”

OMNISCORE: