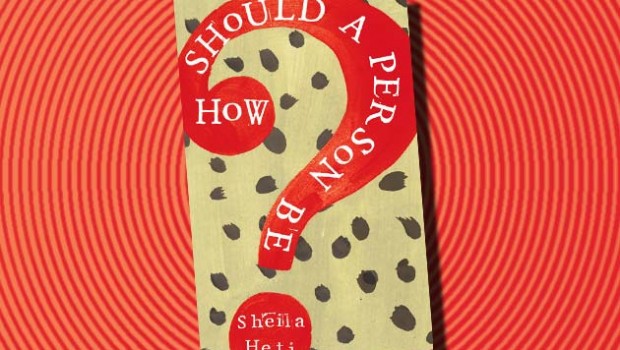

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti

Reeling from a failed marriage, Sheila, a twenty something playwright, finds herself unsure of how to live and create. When Margaux, a talented painter and free spirit, and Israel, a sexy and depraved artist, enter her life, Sheila hopes that through close-sometimes too close-observation of her new friend, her new lover, and herself, she might regain her footing in art and life. Using transcribed conversations, real emails, plus heavy doses of fiction, the brilliant and always innovative Sheila Heti crafts a work that is part literary novel, part self-help manual, and part bawdy confessional.

John Crace’s Digested Read — The Guardian

The Economist

“Just as self-absorption threatens to swamp the tale, a crisis causes her to look squarely at her own sexual and debased life. Her friendship with Margaux, a painter, provides redemption of a kind. Throughout, the reader is beguiled by blunt, sly observations: “Smiling only encourages men to bore you and waste your time.” “The world is full to brimming with its own shit. A little more from me won’t even make a difference.”“

Scarlett Thomas, The Guardian

“Just when you think Heti has been too cute, or one of her many exclamation marks too archly faux‑kitsch, she will come back with something arresting like this: “Let my breasts not satisfy you then. Let my cunt bore you completely, so that even all the other cunts in the world can’t distract you from the boredom that comes over you when you think of mine.” The project of this novel, it seems, is not to be beautiful, or even liked, but to challenge the idea that art should have these effects. Art, it suggests, can be humiliating, banal, low.“

Joanna Biggs, The London Review of Books

“Heti is testing how ugly a novel should be. Can a novel be written in unelevated prose with a California-girl twang to it? Can a novel be made from real conversations and emails? Can a novel be boring but unputdownable? Heti’s book is not so ugly as not to be recognisable as fiction. How Should a Person Be? is a Bildungsroman about two women trying to become artists (‘We do whatever we can to make the other one feel famous’) and as such the reader has questions she wants answered, questions compelling enough to get her through the boring bits …“

David Haglund, The New York Times

“Sheila measures herself against these friends as she tries earnestly to answer the question of her title. “Responsibility looks so good on Misha,” she thinks, “and irresponsibility looks so good on Margaux. How could I know which would look best on me?” She speaks with that questing and ingenuous tone throughout the book, but neither the novel nor its heroine is precious or naïve.“

Kate Saunders, The Times

“Heti is superbly truthful, and shockingly funny — no words were minced in the making of this strange, brilliant book.“

Olivia Laing, New Statesman

“Much has been made in the US of Heti’s boundary games, of her elaborate finessing of fiction and reality. The novel is constructed from multiple materials, including snippets of emails and long sections of dialogue. In its self-referential intertextuality and its offbeat wit, it recalls Geoff Dyer’s Jeff inVenice, Death in Varanasi, as well as Warhol’s bizarre novel a (1968), in which he taped and had badly transcribed 24 hours of amphetamine-fuelled conver – sation between various logorrheic Factory members. As this suggests, How Should a Person Be? is a profoundly ironic production – or, perhaps more accurately, it is a production profoundly concerned with how to live authentically in a world saturated by irony.urately, it is a production profoundly concerned with how to live authentically in a world saturated by irony.“

Lidija Haas, Times Literary Supplement

“Sheila dwells on her most embarrassing qualities, her compliance and neediness, her gigantic, fragile ego, finally deciding that “my life need be no less ugly than the rest”. She observes her own limitations and those of her culture with a certain receptive amusement, rarely biting hard enough – or standing far enough outside – for satire. “

James Wood, The New Yorker

“Since most readers do not know who Heti’s friends are or how Heti herself lives, the characters will appear effectively invented—as Heti doubtless understands. It’s a shame that Heti’s writing, normally pellucid, is so loose here. Of course, this is related to the raw, almost Warholian feel of the book. There is, too, a troubling knowingness, an uneasiness about how seriously the novel should press down on its seriously interrogative title. This sometimes presents itself, interestingly, as a failure of realism.“

John Harding, The Daily Mail

“… a ragbag of random thoughts, minor incidents, bits of plays and explicit sex with little attempt at a plot or indeed any sort of tension to encourage the reader to keep going, and rather than ground-breaking, curiously old fashioned in that it’s surely all been done before. On the plus side Heti does have a wicked sense of humour and some of her one-liners are genuinely laugh out loud.“

Anthony Cummins, The Daily Telegraph

“Sheila decides that in art and writing “you have to know where the funny is” – that’s how she talks – but you have to be fully plugged in to the book’s alternating current of irony and earnestness to know where the funny is when she compares her struggles to the trauma of an abused child or the failure of the Israelites to reach the promised land.“

Doug Johnstone, The Scotsman

“… for all the rather annoying whining, there is something occasionally magical going on here. An abusive on-off sexual relationship with a guy called Israel (which may be a metaphor) is extraordinarily well depicted – the extreme and brutal psychological bullying and submissive tendencies rendered with heart-breaking honesty.“

Hannah Rosefield, The Literary Review

“How Should a Person Be? was published in the United States last year, and much of the praise it received there focused on Heti’s reversal of the established hierarchy of relationships. But her strategy is less radical than it seems. Instead of presenting female friendship as something qualitatively different from the sexual or romantic relationships that popular culture foregrounds, Heti has Sheila and Margaux’s friendship mimic heterosexual courtship.“

Emily Stokes, The Financial Times

“It’s a naivety that Sheila cultivates in her glib prose – and one that, ultimately, leads to confusion; as with an intentionally ugly painting, it’s never clear how seriously to take her impressions. Honesty, we find, can lack self-scrutiny; it can also breed a kind of malaise.“

Holly Williams, The Independent on Sunday

“Examples: “I just did my ugly painting, and I feel like I raped myself.” “I have more respect for your art than I do for my own fears.” “If I want my life to be a work of art, then if I make bad work, it tarnishes my life.” I mean, really – who talks like this?“

Claudia Yusef, The Daily Telegraph

“All of which is wittily articulated, but makes it hard to know when, if ever, Sheila wants us to take her seriously. When Sheila and Margaux fall out over a trivial matter, I find myself waiting for the punchline … Suddenly, the jokes about weeding out all the “ugly people” from their lives feel less self-satirising and more a probable statement of affairs. And, suddenly, the whole enterprise feels less self-aware and less insightful than an episode of Sex and the City.“

Robert Collins, The Sunday Times

“Narrators agonising over how not to be phony, of course, stretch back to Huckleberry Finn, through Holden Caulfield in JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, even, more recently, to the novels of Bret Easton Ellis, whose eerie protagonists are all singularly incapable of feeling authenticity. Yet the paradox of Heti’s novel is that by importing so much so uncritically from her life, she has omitted that crucial distance that makes, for instance, Caulfield so engaging or Ellis’s narrators so creepy. As a result, her whole book feels faker than any fiction she’s supposedly eschewing. “

OMNISCORE: