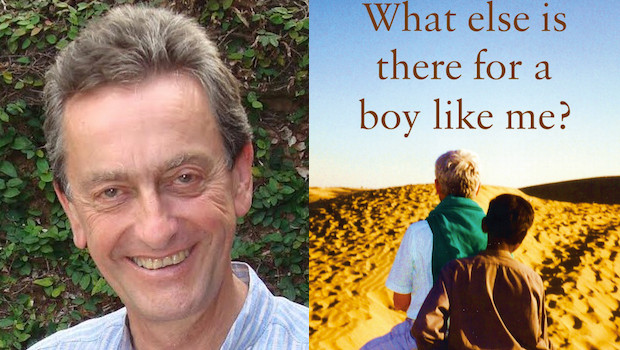

Author Pitch: What Else is there for a Boy Like Me? by Patrick Moon

Many city lawyers fantasise about giving up their jobs to travel; few actually have the guts to do it. Patrick Moon became besotted with India after going there on holiday, and stayed in touch with the young man who’d been his tour guide. His new book describes what happens when he went back to mentor Mohamd. Set among the deserts of Rajasthan, What Else is there for a Boy Like Me? is a sobering tale of where our charitable impulses can lead us.

When and why did you first go to India?

January 1996. It was a complete leap into the unknown. I’d never yet been anywhere outside Europe. But things I’d been reading and picked up from friends had whetted my curiosity, convinced me that I ought to give it a try. Yet everyone I talked to said I’d either love it or loath it and – still on the treadmill as a lawyer — I didn’t want to waste too much precious holiday finding out which. So I went all that way there for just a week (!) doing the classic ‘Golden Triangle’ of Delhi, Agra and Jaipur, with the beautiful lake city of Udaipur squeezed in for good measure. However, I returned a lost cause, entirely besotted. The rest of the world was never going to feel the same again.

What made you fall in love with the country?

This is quite hard to pin down. I think a lot of the many people I meet who are hooked on India would say the same. Of course there are all the superficial attractions like the climate and the food, the landscape and the culture, the vibrant colours, the heady smells… but those are just the things that make it entertaining to be there. They don’t make it necessary to keep going back. Part of the answer, I’m sure, lies in India’s people: their welcoming warmth and good humour; their amusing eccentricity; their stoicism, resilience and inventiveness; and perhaps above all their amazing generosity, especially at the level where they have least with which to be generous. And that, I think, leads to the other part of the answer. I’m convinced that India helped me redefine my values. Indeed, I’m not at all sure that I would ever have made the decisive move to leave the law, if I hadn’t first been to India.

What did your friends make of your decision to quit your job and go back to India?

It was met with a whole range of reactions from shock and dismay to excitement and envy. I was after all abandoning a successful career to start again from zero, with absolutely no idea what was going to come next. I’d been too busy being a lawyer to think about alternatives. I just knew that I didn’t want to wake up one day, aged 60, having done only that one thing with my life. But as soon as I knew that I’d be ‘free’, there was never any doubt in my mind that India was where I was going to spend my winter. It must have been a terrible time for my partner, Andrew, wondering anxiously whether he was still going to recognise the person who’d come back at the end of it; but generously he never tried to hold me back. He’d understood instinctively that I’d never felt so determined about anything in my life. It seemed like the only possible place to try to reinvent myself.

How did you meet Mohamd?

Between that first revelatory week and my exit from the legal profession, I’d managed another two-three week holiday in Rajasthan and Mohamd was simply the guide selected by the local travel agent to escort me round the beautiful city of Jaisalmer. He was a good enough guide – not outstandingly knowledgeable, but clear, conscientious and considerate: perfectly fit for purpose. Yet I wouldn’t really have given him a second thought, if I hadn’t happened to ask him about his background. He came from a primitive, largely illiterate tribe, living in the bleak surrounding desert.

At the age of about 12, he’d quit the family mud hut and taken himself off to the city, enrolling himself in a school and scraping together enough on the fringes of the tourist industry to pay for his keep in a hostel. By the age of 18, when I met him, he’d taught himself quite respectable English, reasonable French and Italian and a bit of Japanese and was the major breadwinner for his parents and numerous siblings. But the future offered only the same tired old trail round the Jaisalmer monuments. He couldn’t see any way of breaking out of this limited world.

How did you plan to help Mohamd?

Mohamd was simply lucky: he was in the right place at the right time. I felt India had given me so much that I wanted to put something back. I knew I couldn’t change the big problems of India, but maybe I could change a small one. I thought, ‘If the boy’s achieved this much on his own, what might he do with a little help?’ So when I got back home, I wrote to him, telling him I didn’t want to steer him in any particular direction but, if a little money (I never said how much) would help him unblock the obstacles to fulfilling his potential – maybe paying for some training or giving him some capital to start a small business – I’d like to try. I knew that the sort of money I’d frequently blow on some trivial treat (I was still a well-rewarded solicitor at this stage, remember!) might actually change someone’s life. And very much to Mohamd’s credit, he wrote back saying he was fine. He wanted to finish his studies and he’d let me know if there was anything I could do for him in the future. In the meantime, would I please keep writing to him? So I did. But, as soon as I knew that I was making this long winter visit, I knew that I had to return to Jaisalmer, so see whether my rash, impulsive offer could be turned into some kind of practical reality.

And what happened?

A lot more than I had bargained for… I started out frankly dreading the reunion with Mohamd. I barely knew him. He was really just a convenient conduit for a charitable impulse. But gradually, as I spent some more time with him, he grew into someone that I really cared about, like a favourite nephew, even the son that I’d never had… So it was all the more distressing to discover that my driver on this journey had taken against him, believing Mohamd to be his own social inferior and therefore undeserving of his passenger’s interest. The driver’s eventual plot to have the boy attacked took me closer to the darker side of India than I’d ever imagined possible.

Meanwhile, poverty and low social status were only part of Mohamd’s problem. He was much more worried about the marriage that his parents were planning for him with a typical, uneducated girl from his desert tribe: a life sentence of incompatibility, as he saw it. He was convinced that, if he could only get to England for a while, he could achieve some success that would outweigh the ‘shame’ of a love marriage. I couldn’t imagine what he could possibly accomplish there, but I’d seen how far he’d already come through his own efforts and felt I had to help him try…

Unfortunately, both of us had seriously underestimated how much of the weight of Indian society was going to be stacked against us. And so, with the book telling two parallel stories – the attempt to change my own life and the attempt to help Mohamd change his – one of these ends well and the other badly.

Looking back, do you wish you’d approached your journey any differently?

I think nowadays I’d be a little more realistic: less idealistic and naive about how things ‘work’ in a country like India. But the key question, I think, is: was there ever a point where a different kind of intervention on my part could have brought about a different outcome for Mohamd? I’ve asked myself this many times over the intervening years and I don’t believe there was anything that I could have done differently which would have averted the eventual tragedy. But that doesn’t mean I wouldn’t make the same attempt all over again. I passionately believe that, in these situations, it’s better to stick your neck out than simply walk away because it’s all too difficult; better to try and fail than not try at all.

What has your time in India taught you about yourself?

It’s given me a clearer, stronger sense of what’s important in life. And every time I go back (I’ve just had a month in Kerala, which has given me an idea for another book!) it’s a chance to reconnect with those values. It also lets me ‘recharge’ on India’s seemingly inexhaustible energy, to get me through another year!

Why did you decide this story needed to be told?

Nothing in my life has touched me more deeply than the events recounted in this book. So, although there’s plenty of comedy and warm affection for India in the book, it’s a very different read from my earlier ‘feel good’ books about wine and food in the Languedoc, Virgile’s Vineyard and Arrazat’s Aubergines. Mohamd himself once urged me to write a book about the problems that he and his kind were facing and, over the years, whenever I’ve told people his story — how the unfortunate, unsuitable marriage ruined everything — so many people have said to me, ‘But surely he could always have said no’. I felt I owed it to Mohamd to explain to a world that had never heard of him why he couldn’t and didn’t. And why that led to disaster.

What sort of readers will your book appeal to?

Well, lovers of, and travellers to India obviously; but I hope its appeal is much wider than that. It should strike a chord with readers who’ve travelled to any part of the less privileged world and been saddened by the same kind of under-realised potential in the people they meet. I think there’s a resonance too for any readers, particularly those without children, who have ever felt this impulse to nurture and mentor a younger person. And of course, while it’s definitely not a ‘self-help’ book, it should interest anyone who’s ever fantasised about changing the course of their lives in mid-career, without necessarily being crazy enough to do it! Perhaps above all, for readers who’ve never really thought about any of these things, it’s quite simply a strong and moving human story, which just happens to be true.

What are your favourite books about India?

My favourite non-fiction introduction to the country is Trevor Fishlock’s ‘India File’, though sadly (and scandalously) it’s out of print. On that first trip to India, Andrew and I both tried to read it simultaneously, each of us pouncing on it avidly whenever the other was in the shower or whatever, with two different bookmarks moving through the book in competition. On the fiction front, Rohinton Mistry’s ‘A Fine Balance’ is not just my favourite novel about India; in my view (I said I was given to sticking my neck out!) it’s the best novel of all time.

What Else is there for a Boy Like Me? is published by Matador.

Buy What Else is there for a Boy Like Me?

The Omnivore helps readers discover the best indie authors. If you would like to be featured on Author Pitch email authorpitch@theomnivore.com