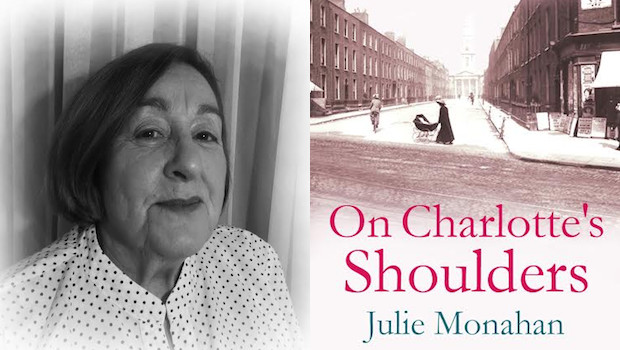

Author Pitch: On Charlotte’s Shoulders by Julie Monahan

Julie Monahan’s account of growing up in a desperately poor family in Dublin during the 1940s and 1950s may have been dismissed by mainstream publishers as yet another misery memoir but, she argues, it is much more than that: not only does it have an undercurrent of humour, it is an important slice of social history.

Tell us a bit about yourself:

A few years after I came to the UK I studied at evening classes for O and A levels and went on to do a degree in Sociology at London University. I followed as career as a social worker and was appointed as a magistrate some years later. I am now retired from both roles. I have a son and a daughter and one grandson. I live in East London. I do a bit of voluntary work and try to keep my mind active by attending various classes: novel writing, French and Tai Chi to name a few. I also recently landed a little job in a nursing home helping with evening meal and do about ten hours a week. In between times I try to do a bit of work on a second volume: my life as a naïve, uneducated young girl struggling to adapt to a new life.

Who are your favourite authors?

I studied English literature as an adult and have enjoyed reading all the classics. I particularly enjoyed the work of Thomas Hardy. My tastes in reading matter now are somewhat eclectic but I will read anything by Sebastian Barry, Anne Enright, Alice Munro, Roddy Doyle, Colm Toibin and Kazuo Ishiguro. I also enjoy biographies in particular those by Claire Tomlin – Dickens and Jane Austen. I occasionally read poetry: W B Yeats and Seamus Heaney are two of my favourites. I have written a few poems and published a small volume at my own expense. I’m not too keen on short stories but paradoxically my favourite book is James Joyce’s Dubliners.

What book are you reading now?

I’m currently doing a novel writing course so the books I’m reading at the moment are related to that. Fortunately, they are mainly by authors I enjoy: F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby; The Hours by Michael Cunningham; Brooklyn by Colm Toibin; Good Behaviour by Molly Keane; The Siege of Krishnapour by J.G. Farrell; The Talented Mr Ripley by Patricia Highsmith … to name but a few! I recently started rereading Jane Eyre, my interest sparked by having watched a filmed version which barely scans the main story line and fails – as all films will – to distil the brilliance of the writing, if somewhat turgid in part and alien to the modern ear.

What made you sit down and write your memoirs?

I started writing a few bits about my childhood for an autobiographical writing class I attended some years ago. I enjoyed writing and the pieces I prepared were always well received by my classmates and tutor. This gave me some encouragement to set it all down in chronological form rather than just recalling memories. It was a real problem finding a ‘voice’ to write in. I wanted to get away from the kind of memoir which began – ‘I remember when…’ ‘One day…’ ‘We used to do…’ ‘My mother/father would…’ etc. It took some time for me to alight on using the naïve child’s point of view. I wanted to take the reader on a journey through my childhood alongside me and hope that she/he would emotionally engage with the child and her family.

I also thought it was time for a memoir from a female perspective. Although there are many books out there written by Irish women, they tend to written by middle class women, or are tabloid style stories of the shock, horror type. Potboiler tales of depravity or of sexual/physical abuse, drug addiction etc. with an emphasis on the lurid.

I wrote the memoir on and off in the last ten years or so, always encouraged by my husband and tutors to finish it.

Was it a difficult book to write?

It was a difficult book to write from the emotional point of view, but an easy one from the creative point of view. In many ways the book almost wrote itself and I never had any difficulty with the material. Soon after I started the book my mother’s voice took over. I never set out wanting to write about the bravery and courage of my mother: it was originally conceived as a book about how I overcame my deprived upbringing and became educated etc. But the perspective changed as I was writing and I had many tearful moments as I set it down the memories. There was laughter as well, so I have tried to convey the humour as well as the misery.

You say the events in On Charlotte’s Shoulders are dramatised but are all based on reality. How much of your book is fictional, and how much really happened?

The entire book is based on reality and indeed there was a lot more that never made it into the book! By dramatised I mean I have attempted to ‘show’ rather than ‘tell’ incidents and events. By using the naïve voice I hoped to place the reader directly in the beating heart of the family, to experience the same emotions I went through as a child. It would make a very boring book if I just related the events in a matter-of-fact kind of way. All the events described are real; nothing is made up. That is not to say I have perfect recall of the exact times and incidents. There is some compression of detail and conflation of timelines e.g. my childhood was punctuated by the comings and goings to England by my father and later on my older sisters and brother so I don’t think I managed to record exactly who was at home and when, but the overall departures and returns I wanted to convey as truthfully as I could. And although I recall my mother working as a cleaner in a convent in Eccles Street when I was very young, I cannot be sure of the whys and wherefores. I do recall life in the slum tenement and a visit from the housing officer, but the conversation between my mother and him is imagined as so many conversations throughout the book are.

I wanted to capture the tone, the style, the language and the emotion. Much of the dialogue has had to be imagined but I think it gives a good and honest account of the nuances and language used. Some scenes are imagined e.g. the scene where I describe the actual move from Dorset Street to Cabra on a horse and cart with my Uncle Benny pointing out well known buildings – churches, hospital and Mountjoy prison – is imagined but the ride on the horse and cart is real.

I was in Linden Convalescent Home for eight months as an eleven year old girl, I did spend three months in St Kevin’s hospital when I contracted Bell’s palsy and Jimmy did fall in love with me during my three months in St Kevin’s hospital when I was there for treatment.

The influence that Vincent had on me is very real. The letter extracts are word for word exactly as written. In fact I still have all his letters in my possession. But I hold my hand up to one fake scene which occurs towards the end of the book, shortly before I was discharged from hospital where I write of him meeting my mother: he never did although she knew all about him. This piece was inserted at the request of my editor who wanted ‘a bit more about Vincent’.

I think the art of memoir writing is creative in many ways. Memories are sieved and once encapsulated in written form they tell their own truth. It would be hard to really convey the dire poverty, the destitution, the addiction to alcohol which took precedence in my father’s life over supporting his large family. As well as the hold of the Catholic Church over so many aspects of our lives, though my father was never a believer as is shown throughout the book. So many memories seemed to be triggered off as I wrote and as I say, it would be had to exaggerate the extent of the poverty, the insecurity and turmoil of our upbringing.

How has Dublin changed since your childhood?

Dublin is now a much more affluent city than it was when I grew up. The old tenement slums have long since vanished from Eccles Street, Hardwicke Street and Dorset Street the streets of my early childhood – now replaced by corporation flats in the main. The education system has improved considerably with free Secondary schooling for all. In my day Secondary schooling had to be paid for and at primary level the education was very basic.

Another change is the role of the Catholic Church: it doesn’t have the same power these days. In earlier times, the Church had a lot of control over the education system and social issues such as birth control and laws relating to marriage. There is now a well-developed system of social welfare for families and older people. Although the country was slower than most to accept birth control, separation/divorce and single parenthood, these freedoms are open to all today. In my time a lot of the welfare roles were performed by various charities with a minimum of state provision. It has to be said that they performed a very important function and on the whole they did good job considering the enormous social problems that existed then.

I am also aware that media in general is freer from interference by the church and state and the censorship that existed years ago has long since vanished. Overall Ireland has become a very broadminded country where human rights are readily recognised by all agencies and service providers.

How has your family reacted to your book?

I have to be honest and say I do not have much contact with my surviving siblings. My brother Mikey died a few years ago as well as Lottie and Mary. The only one I have regular contact with is my younger brother – Harry in the book – who still lives in Dublin. He was never very happy about me writing of our childhood; he objected to the family’s dirty linen being washed in public. His truth is somewhat different from mine, a commonplace in many families where members have different memories. I decided to go ahead anyway despite his opposition as I thought the book is not only a memoir but an important piece of social history.

What made you choose your publisher, Acorn Independent Press?

A couple of years ago Penguin in Ireland showed some interest in publishing the book but decided not to on the grounds that there were already too many misery memoirs on the market! However they did express an interest in looking at Volume two. I never intended to write a ‘misery memoir’ really. I just wanted to record life as it was for large working class families who struggled daily to survive. Besides, there is quite a bit of humour threaded throughout the book.

I decided to go with Acorn who were new to the field of independent publishing and offered a full service that included editing, proofreading and marketing. Acorn had a mammoth task really in editing the book which originally ran to nearly 700 pages! They also helped me sort out the timeline and repetitions which were a big problem for me in a book which was written over a number of years. The book has already returned more than my original outlay I’m pleased to say.

Imagine your ideal reader: which authors do they enjoy?

A difficult question! During the writing of the memoir I had in mind readers who enjoy ‘real life’ stories, someone who also reads more popular fiction rather than hard-to- engage with contemporary literature. Initially I saw my reader as an older person – perhaps female; someone and might be able to identify with the writer. I suppose I thought the book might have more appeal to an Irish audience or reader of Irish extraction. In fact my editor has aimed the book at this market believing there is a wide readership for memoirs that are readable and easy to identify with. Although not written as a historical document I now realise the book might be seen as an important piece of social history and therefore might appeal to a more academic readership.

Read an extract from On Charlotte’s Shoulders

Buy On Charlotte’s Shoulders from Amazon (ebook and paperback)

The Omnivore helps readers discover the best indie authors. If you would like to be featured on Author Pitch email authorpitch@theomnivore.com